Introduction

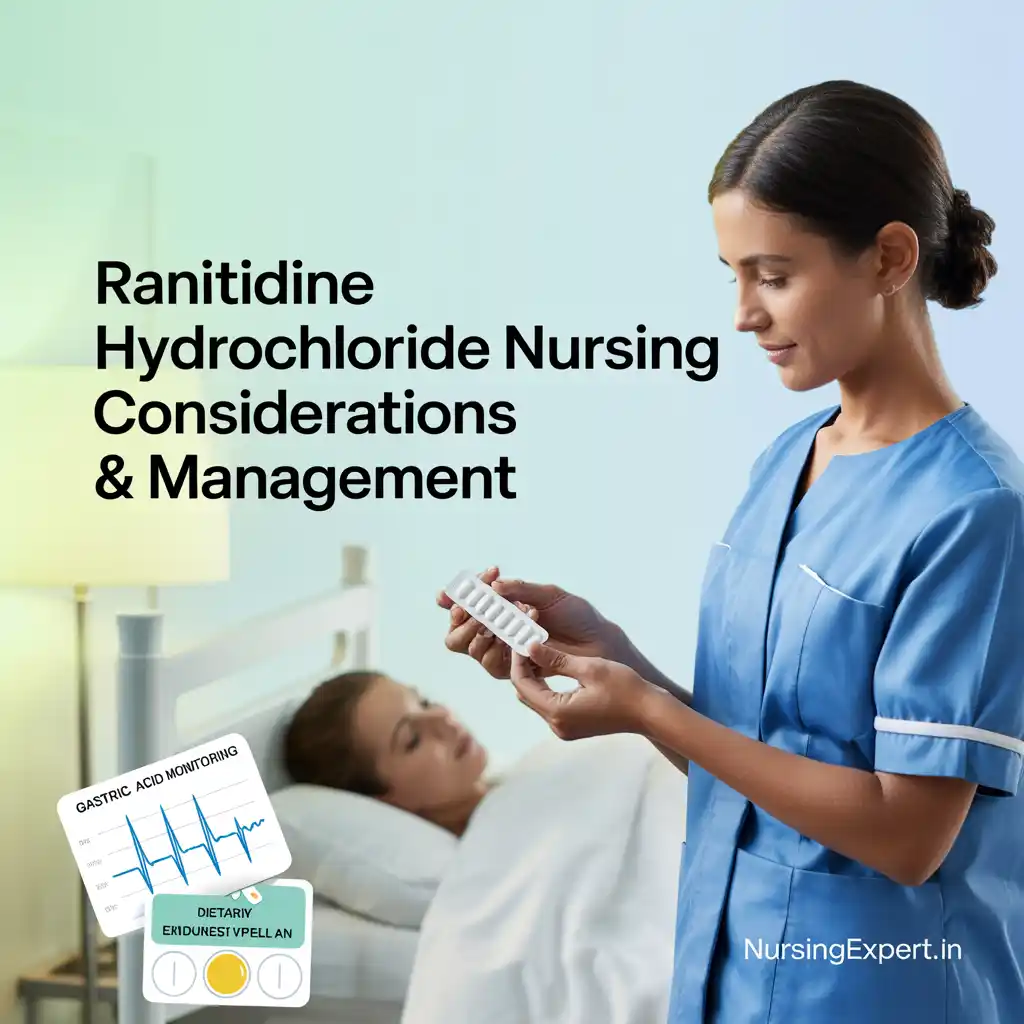

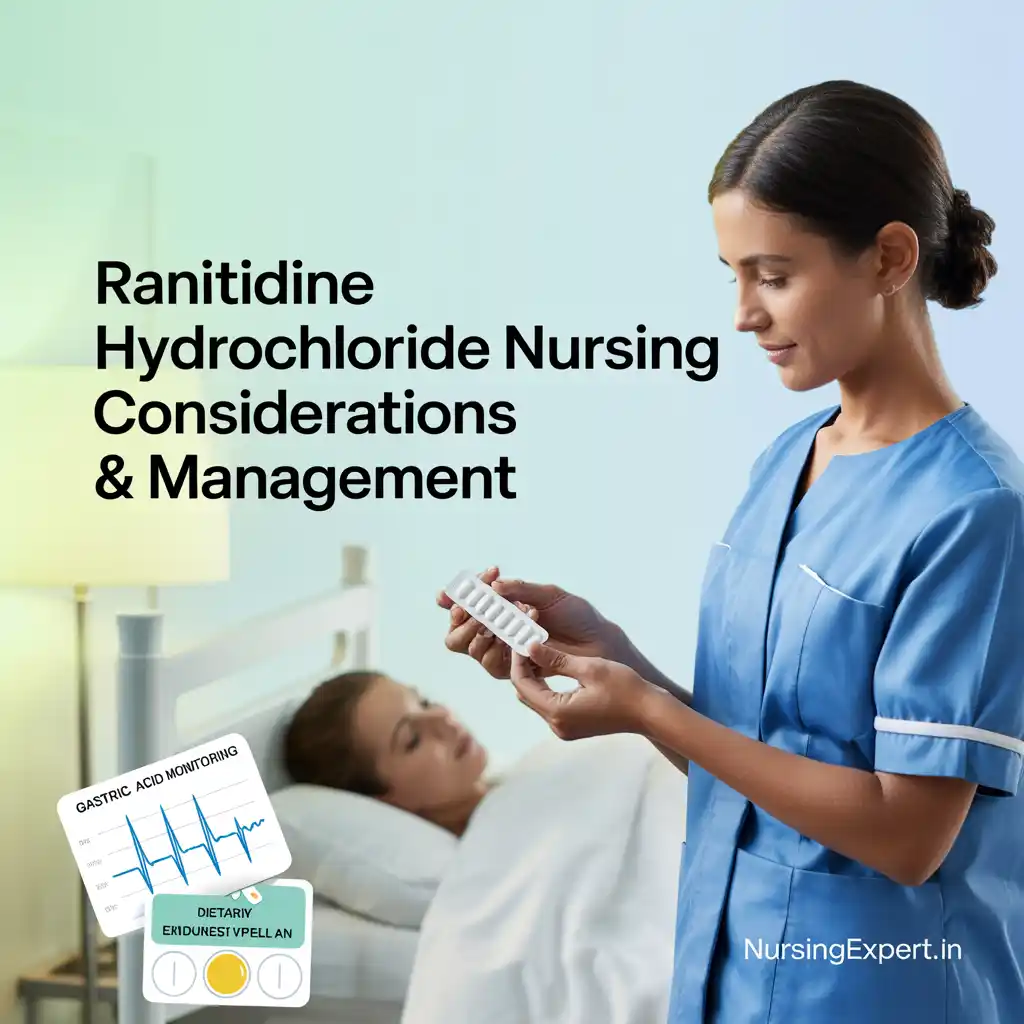

Ranitidine hydrochloride, widely recognized by its brand name Zantac, was once a cornerstone in the management of acid-related gastrointestinal disorders. As a histamine-2 (H2) receptor antagonist, it worked by blocking histamine receptors on parietal cells in the stomach, reducing gastric acid production. This mechanism made it highly effective for treating conditions such as peptic ulcer disease (PUD), gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. It was also used to prevent stress ulcers in critically ill patients and as an adjunct in managing allergic reactions.

Thank you for reading this post, don't forget to subscribe!

Introduced in 1981 by Glaxo (now GlaxoSmithKline), ranitidine quickly gained popularity due to its efficacy, longer duration of action, and fewer side effects compared to its predecessor, cimetidine. Available in both oral and intravenous (IV) forms, it was a versatile option in various clinical settings. However, in 2019, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) identified low levels of N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA), a probable human carcinogen, in some ranitidine products. This led to recalls, and by April 2020, the FDA requested its complete removal from the market. Today, ranitidine is no longer available in many countries, replaced by alternatives like famotidine and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).

Although ranitidine is no longer in use, understanding its nursing considerations remains valuable for educational purposes and for applying similar principles to current medications. This article explores ranitidine’s historical role, its nursing management, and the lessons learned from its withdrawal.

History and Development

Ranitidine was developed in 1976 as an improvement over cimetidine, the first H2 receptor antagonist. Cimetidine, while effective, had limitations such as a short duration of action and significant drug interactions due to its inhibition of cytochrome P450 enzymes. Ranitidine addressed these issues with a longer-lasting effect and a safer profile, making it a preferred choice by the time it hit the market in 1981. It became one of the best-selling drugs globally, widely available over-the-counter for mild heartburn relief.

The discovery of NDMA contamination in 2019 changed its trajectory. NDMA, a byproduct of certain manufacturing processes, was found to increase over time, especially under high temperatures. This prompted voluntary recalls by manufacturers and the eventual FDA mandate to withdraw all ranitidine products, marking the end of its widespread use.

Indications

Ranitidine was historically prescribed for several conditions:

- Peptic Ulcer Disease (PUD): It promoted healing of gastric and duodenal ulcers by reducing acid levels, alleviating pain, and preventing recurrence during maintenance therapy.

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD): Ranitidine relieved heartburn and regurgitation while aiding in the repair of erosive esophagitis caused by acid reflux.

- Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome: This rare disorder, involving excessive acid production due to gastrin-secreting tumors, was managed with ranitidine to control acid output.

- Stress Ulcer Prevention: In intensive care settings, it prevented stress-induced ulcers in critically ill patients, reducing the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding.

- Allergic Reactions: As an adjunct to H1 antihistamines and epinephrine, ranitidine helped manage severe allergic responses by blocking H2 receptors.

Its broad utility made it a staple in gastrointestinal care before its discontinuation.

Dosage and Administration

Ranitidine’s dosage varied by condition and administration route:

Oral Administration

- Peptic Ulcers: 150 mg twice daily or 300 mg at bedtime for 4-8 weeks.

- GERD: 150 mg twice daily, adjusted for symptom severity.

- Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome: Starting at 150 mg twice daily, with doses up to 6 g daily in severe cases.

- Maintenance Therapy: 150 mg at bedtime to prevent ulcer recurrence.

Oral ranitidine could be taken with or without food, available as tablets, capsules, or syrup for patients with swallowing difficulties.

Intravenous Administration

- Acute Conditions: 50 mg every 6-8 hours, diluted and infused over 15-20 minutes.

- Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis: 50 mg every 6-8 hours or as a continuous infusion in critical care settings.

For IV use, nurses diluted ranitidine in a compatible solution (e.g., 0.9% sodium chloride) to 0.5 mg/mL, ensuring slow infusion to avoid hypotension or bradycardia.

Nurses were responsible for verifying dosages, preparing IV solutions, and educating patients on proper oral administration.

Contraindications and Precautions

Ranitidine was contraindicated in patients with hypersensitivity to it or other H2 antagonists. Key precautions included:

- Renal Impairment: As ranitidine was primarily excreted by the kidneys, accumulation risked toxicity in patients with reduced renal function. Dosage adjustments were:

- Creatinine clearance (CrCl) 30-50 mL/min: 150 mg daily or 50 mg IV every 12 hours.

- CrCl <30 mL/min: 150 mg every 24 hours or 50 mg IV every 18-24 hours.

- Hepatic Impairment: Used cautiously, though significant dose adjustments were rarely needed.

- Elderly Patients: Increased risk of CNS effects (e.g., confusion) necessitated close monitoring.

- Pregnancy and Lactation: Category B drug, used cautiously in pregnancy; excreted in breast milk, requiring consultation with providers.

Nurses assessed renal function and adjusted care plans to ensure patient safety.

Adverse Effects

Ranitidine was well-tolerated, but potential side effects included:

- Common:

- Headache

- Dizziness

- Constipation or diarrhea

- Nausea

- Serious (Rare):

- Hepatotoxicity (e.g., hepatitis, jaundice)

- Blood dyscrasias (e.g., thrombocytopenia)

- Cardiovascular effects (e.g., bradycardia with rapid IV infusion)

- CNS effects (e.g., confusion in elderly or renally impaired patients)

Nurses monitored for these effects, particularly during IV administration, and reported significant changes promptly.

Drug Interactions

Ranitidine had fewer interactions than cimetidine but still required attention:

- Reduced Absorption: Affected drugs needing an acidic environment, e.g., ketoconazole, itraconazole.

- Metabolic Effects: Mildly inhibited cytochrome P450, potentially altering levels of warfarin, phenytoin, or theophylline.

- Other: Increased procainamide levels or prolonged benzodiazepine effects.

Nurses reviewed medication lists and collaborated with pharmacists to manage interactions effectively.

Nursing Considerations

Nurses played a critical role in ranitidine management, focusing on:

Assessment

- Pre-Therapy: Evaluated medical history (allergies, renal/hepatic function), symptoms (e.g., epigastric pain), and baseline labs (e.g., CrCl).

- Critical Care: Assessed for gastrointestinal bleeding risks in ICU patients.

Administration

- Oral: Ensured patients took doses as prescribed, advising on flexibility with meals.

- IV: Diluted and infused slowly, monitoring infusion rates to prevent adverse reactions.

Monitoring

- Efficacy: Tracked symptom relief (e.g., reduced heartburn).

- Safety: Watched for side effects, especially in high-risk groups, and checked IV sites for complications.

- Renal Function: Monitored in patients with kidney disease to adjust doses.

Patient Education

- Explained ranitidine’s purpose and administration.

- Advised reporting severe side effects (e.g., confusion, bleeding).

- Stressed adherence and follow-ups for long-term use.

Case Study: Managing a Patient on Ranitidine

A 65-year-old male with a bleeding duodenal ulcer and mild renal impairment (CrCl 40 mL/min) is prescribed IV ranitidine 50 mg every 8 hours.

- Assessment: The nurse notes renal impairment, confirms dosage appropriateness, and checks for bleeding signs (e.g., melena).

- Administration: Dilutes 50 mg in 100 mL saline, infuses over 20 minutes, and monitors vital signs (BP 140/90 mmHg, HR 80 bpm).

- Monitoring: Observes for hypotension during infusion and symptom improvement post-dose.

- Education: Explains ranitidine’s role in ulcer healing and advises reporting new symptoms.

This scenario highlights tailored nursing care based on patient-specific factors.

Alternative Therapies

Post-withdrawal, alternatives include:

- H2 Antagonists: Famotidine (safer profile), cimetidine (more interactions), nizatidine.

- PPIs: Omeprazole, pantoprazole—more potent options for severe cases.

- Antacids: For mild symptoms.

Nurses assist in transitioning patients by explaining alternatives, monitoring responses, and addressing concerns.

Lessons Learned from the Ranitidine Recall

The recall emphasizes:

- Safety Vigilance: Nurses must track drug alerts.

- Communication: Clear explanations ease patient transitions.

- Adaptability: Quick shifts to alternatives are essential.

- Education: Ongoing learning ensures current practice.

These lessons enhance nursing practice beyond ranitidine.

Conclusion

Ranitidine hydrochloride was a key player in acid suppression therapy, with nurses central to its safe use through assessment, administration, and education. Its withdrawal due to NDMA contamination underscores the need for vigilance in medication safety. While replaced by alternatives like famotidine and PPIs, ranitidine’s nursing considerations remain a valuable framework for managing similar drugs, ensuring effective patient care in an evolving healthcare landscape.